Over the summer [July 21 - August 16,

2000] Matt Childers and Chris Van Leuven of Boone, NC spent a month climbing in the remote Logan Mountains in the Northwest Territories of Canada.

The climb was financed with grants from the American

Alpine Club and Polartec. After climbing the classic Lotus Flower Tower in a day (23 pitches 5.10)

Matt and Chris ran headlong into the worst storm of the season on the summit. After recovering from

this epic, they flew to a nearby area to climb a new route on a feature dubbed the

Minataur, where they threw themselves at epic #2.

|

|

|

FA:

Run For Cover (V 5.10 A2) 1,650ft.

Matt

Childers and Chris Van Leuven; August 10-11, 2000.

Northwest Territories, Canada. Southeast Face of the Minataur: N61o52'31"W127o40'38" |

By: Chris Van Leuven

Matt and I felt the humming in our ears and static in the air at the same time but remained silent more out of curiosity than shock. It couldn't be - we're gonna' get struck by fucking lighting - the thought came to us. Visibility was down to 10ft, and we couldn't find the anchors to get back down the 15 rappels to the ground. Hail and snow had been falling off and on intermittently for hours, and now that we were on the summit of the Lotus Flower Tower in a full gale.

Matt climbed down 15 feet unroped over the edge of the tower. It began to hail again, and it stung our hands and faces. The wind was howling so loud we had to yell even when we were standing near each other. After a few minutes he called up that he had set the anchor. I followed, eyes feeling like marbles. I couldn't fathom blinking as to let my guard down, and in that nuance of time; a foot could slip, a boulder dislodge, a lighting bolt could strike. I clipped myself into the two stoppers and waited as Matt went down first.

After hours of rappelling and fighting hypothermia we finally got back to the ground at midnight.

A week later of constant rain we got a break in the weather and flew 40 minutes southeast to the

'New Area' to climb the Southeast face of the Minataur, a 1,600ft wall that had never been climbed, except by a slog up the north face snow gully. Matt got word of this area when thumbing through old alpine club journals and talking to a friend who had been to the area previously. His friend told us of a clean, steep big wall that had never been climbed. Matt invited me on the trip while we were climbing together in Yosemite a year ago. I jumped on the chance. A week later of constant rain we got a break in the weather and flew 40 minutes southeast to the

'New Area' to climb the Southeast face of the Minataur, a 1,600ft wall that had never been climbed, except by a slog up the north face snow gully. Matt got word of this area when thumbing through old alpine club journals and talking to a friend who had been to the area previously. His friend told us of a clean, steep big wall that had never been climbed. Matt invited me on the trip while we were climbing together in Yosemite a year ago. I jumped on the chance.

We barely slept the night we arrived in the new area. We tossed and turned, or lay silent, unaware the other was in the same predicament. When the alarm sounded we had been asleep an hour or so. We crawled out of the tent at 4AM, Matt started the coffee and I began gathering items for us to carry up. By the time we had finished our coffee and ate some gruel - usually consisting of leftovers from the night before and some oatmeal or grits, I packed up 3 ropes, many heavy pitons and other general hardware into our two packs, overloading them considerably. We could barely lift them even though we had been getting significantly stronger in the prior weeks of our trip.

We trudged out; backs straining, trekking poles in hand. Our first obstacle was a series of body size boulders we had to climb over just outside of our campsite. After that we walked through a marsh for a quarter mile. We filled up our water bottles from the most powerful flowing stream. Then up some loose talus to gain a ridge that acted as a dam for a breathtaking alpine lake on the other side. The lake was sky blue, and its banks on all sides consisted of large gray talus. We skirted along its banks and pondered which way we would have to go up the upcoming slab to gain the next talus field which led to the wall. We had been hiking for about two hours, the talus climbing had slowed us down as did finding the best way through the stream.

It was then we started to hear loud banging. We looked up the gully that we had considered climbing to see a van size boulder ricocheting the canyon walls. Other rubble followed in its path. After about 15 seconds of watching the havoc unfold the boulder and debris settled down at the base of the lake. All was silent again; an uncomfortable silence as nothing cared of this destruction except for us. A few minutes later we began hiking again, freshly adrenalized.

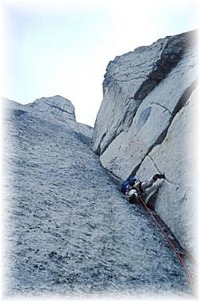

After five and half hours of hiking we reached the base of the wall. We prepared the ropes. We had spied our line after only about fifteen minutes with binoculars when we were resting by the lake earlier in the day. With so many features covering the wall we were confident at making progress quickly. All the features meant that we were going to be heading into very loose territory. We narrowed our line down to what looked the least loose.

I covered my harness and shoulder sling with the proper gear and made sure to bring along a few pitons to drive into the dirt-choked cracks; also a nut tool (the most important tool on our rack) to dig dirt out of cracks so I could to get gear in. I grabbed dirt globs, jammed my hands into cold abrasive cracks. Dirt and grime was forced below my fingernails as I fought for security, causing my nails to pry back and sting. After over half a rope length of general suffering I found a place to build a belay without resorting to drilling a bolt.

Matt jugged up. As he followed I looked up to what the next pitch would bring; a flared chimney and offwidth with some noticeable loose rock and sections that appeared to require some direct aid. The rock

steepened to vertical at this point.

Matt began his pitch. He grunted and forced his body into the flare. Every so often he would call for me to send him up a cam from the belay. After two hours of him fighting to get placements in the dirty cracks he finally called for the last cam that I had. My anchor was now non-existent and I made sure to keep my boots dug into the grassy sloping ledge that I was perched on.

"Line's fixed".

I clicked my jugs onto the rope and followed, relieved to finally have some security. I cleaned the pitch and then we made the decision to call it a day. We were exhausted and hungry. We had made 70 meters of vertical progress. We took all of our remaining hardware down from the wall to keep it from oxidizing again in case a storm blew in overnight.

Morning came sooner than either of us expected. We dragged our weary bodies out of the tent guided by blurry, sleep filled eyes and started the morning ritual of coffee and slop at the usual time of 4AM. Our loads were about 20 pounds lighter than the previous day, and we decided that if we didn't pack sleeping bags with us and just wear all of our clothes to bed (which would be in the portaledge anyway - with expedition fly) then we would be fine for the 4 hours of darkness; thus we wouldn't have as much shit to carry up and back down. We found this to be quite rational too because the evenings had been so warm recently that we only had to wear one fleece jacket to keep warm when hanging around camp.

After a bicep burning jumar, I changed into my free shoes and eyed the next pitch. It looked more intimidating than any lead I had ever done.

I climbed off the belay, as free as I could, relying on grabbing the occasional protruding knob and pasting my feet on the grainy depressions on the face. There was a 10ft tall loose flake about 20 feet above the belay. I fought with fist jams and laybacking up this crack until I reached the flake. I hammered in a Lost Arrow in a seam which went in just to the tip, and tentatively weighted it. Rationalizing that if it pulled I would fall on a good cam I threw chance to the wind, clipped my slings to it and climbed up onto the placement. I lightly banged my hand on the loose ear to my right. It echoed like a large drum and quivered, threatening to fall if I applied any more force to it. I ascended my slings as high as I could get and dug for more placements in the muck and crud. After half an hour or so fighting to get past the flake, crimping on face holds and trenching out placements I got in a few fair small cams and continued up; initially being forced to free climb - via layback - for fifteen feet until I could get more gear. Then the crack opened up and I deployed the largest gear on our rack. Half laybacking, half body wedging - sticking my knee in the crack, stacking hand jams, and tugging on the cams when I could to gain upward progress and committed to the free climbing.

There was a golden flaky scar marking recent rock fall and no gear placements sufficient to build a solid anchor. I looked up to see a ugly 4 inch thick flake extending out to make a chimney offwidth which gave the impression that it could fracture with too much outward

pressure. 'Please don't let this flake fall apart.' After an additional 10ft of desperate climbing all the while trying to convince myself that I was safe, I clutched the top. It could still topple - I repressed this thought, and mantled it. Finally gear became available and I shoved a few small cams into a flake. I balanced and pulled my way across a ledge by grabbing grass and dirt broke out my nut tool and began to excavate a belay out of the 3 cracks in a dihedral. "Off belay."

I hauled and Matt followed. We set to the chore of organizing gear while debris tumbled into the canyon below us, as a result of the glacier at the base. This always unnerved us as no matter how much we heard it, we always took cover in one way or another, not knowing where the debris was falling from.

"Watch me closely off the belay."

"I got you man, don't worry."

Matt crawled out over me up into the dihedral, there were loose blocks shoved in the cracks. After much struggling Matt got past the blocks and climbed onto another ledge. From here he joined yet another system of cracks, which appeared to lead to the top 1,000 or so feet away. Matt crawled out over me up into the dihedral, there were loose blocks shoved in the cracks. After much struggling Matt got past the blocks and climbed onto another ledge. From here he joined yet another system of cracks, which appeared to lead to the top 1,000 or so feet away.

I didn't see him for the next hour or two. I stood at the belay trying to keep warm, munching on peanut butter and crackers, sipping on water and squirming to get comfortable. He hacked dirt clods and rocks from the crack. Finally he didn't move for awhile. 'thank god' I thought to myself, 'he's reached the belay.'

"Send me up the bolt kit."

'What pain in the ass.' I grumbled to myself and dug it out, and prepared to send it up.

"Never mind... I got some gear in... lines fixed." I jugged up the line, and got to work organizing for my lead.

I maneuvered over him and started into a beautiful splitter hand and finger crack in the back of a dihedral. I fixed the line on a few cams and a stopper and Matt followed.

"Man, I can not believe this" he said eying the next pitch. We organized in silence. He climbed delicately as he could as to avoid the spike of rock that was positioned almost directly over our heads ready to break off at anytime and kill us.

"Watch out!"

Surprised and ready for the worst I huddled into the fetal position and waited. A block dislodged unexpectedly. He pushed it away from the wall and it fell over my head. He continued into more loose climbing on questionable gear.

'Okay if he falls now he's going to rip out his gear and clobber me.' I thought to myself. Finally he fixed the line.

Looking up I didn't like what I saw at all. More rock fall scars with obvious debris left over. It looked rotten, however the idea of getting it done beat the idea that I'd have to lie in the portaledge all night and stare at my state of affairs and not sleep a wink.

I committed myself to free climbing past two large loose blocks. I put my foot on a baseball size knob which broke off immediately and almost hit Matt. I crimped past the loose blocks on tiny creaky edges, forearms throbbing. 'This is the stuff that nightmares are made of' I thought to myself. I stood one foot in the rock dust right near a loose block and studied the crack above for more placements, then looked down at Matt. I managed a few more crimpy moves and was finally past the

blocks. The terrain eased off after I passed the blocks and continued up the crack until it slabbed out into a sea of loose terrain.

"I'm gonna take us out of this system, it looks like garbage ahead". I traversed into a chimney system to our right. I found a good place for an anchor and Matt came up.

We set the portaledge up inside the expedition fly. After a bit of struggling to get everything set up properly we finally crawled inside, ate a can of dinner and fell asleep in our clothes. I had the relative security of a

bivy sac and Matt wrapped himself in a tarp. We had been on the go for 20 hours We fell asleep instantly.

"Matt, I'm really cold." I looked at my watch it was 3AM.

I opened up the zipper on the portaledge fly. "Oh god." The dread in my voice came out with no attempt to stop it. It was completely white outside. Our fly had a few inches of snow stuck to it. We beat at the fly and snow fell off in sheets . I looked outside, I couldn't see anything but white. we agreed to wait until we couldn't stand it anymore and then retreat. By noon we set out. Matt stepped out of the relative safety of our abode first. The wind was howling, snow blew into the ledge.

"That's it, we're committed, I'm soaked," he said within a minute of leaving the ledge. Carabiners were frozen shut, I took out my hammer and started to bash ice off of everything, including our ropes.

I tossed down the ropes after we had properly threaded them through the anchor - which was made up of cams. Matt went down first and I followed.

I got down to the next rappel station and pasted my feet onto the muddy, snowy, sloppy ledge; we shoved two more cams off the rack into the crack and Matt went down first again.

A few hours later we were back on the ground. We had left 6 cams. The next two days we rested.

The following morning we woke up at 4AM, choked down coffee, breakfast and hiked up. We got to the base faster than we had previously and jugged up our ropes.

We fired off our pitches. Much of the bite of the unknown was gone, also we had many of the cracks dug out so placing gear was much easier. By 5PM we had reached our high point. Matt led the next pitch, nearly a rope-length lead on the best rock quality we had encountered so far. He built the anchor over a spacious ledge that, though sloping, we could walk around on. We set up the portaledge, coiled the ropes and put them in the haulbag after unloading it. We ate dinner and crawled into our sleeping bags. A light snow began to fall as we drifted off to sleep. Dawn came with clear skies.

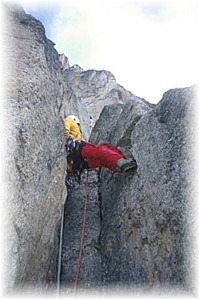

We left the ledge deployed and got to work organizing after a quick breakfast of Clif Shots, an energy bar each and some water. I led into a vegetation filled chimney off the belay and then balanced across a narrow ledge that led into an offwidth. Then back into another chimney and eventually rope drag got too bad and I built a belay. Matt's lead brought him further up the chimney system; he forced his body past blocks so loose I was sure he would cut one loose. I couldn't see him after awhile, only all the sharp edges and teetering blocks that the rope ran through.

"Off belay."

When I reached the belay I was beginning to get a masochistic thrill out of unpleasant climbing; I gave the next pitch a look over. It consisted of a rotten, wet body sized flare on the right or a finger crack on dubious rock on the left. Both were capped by a roof that looked like it might go free or could require drilling. I racked up and took off. I fought to keep my body in the flare but it kept trying to spit me out with its slippery, oozy moss. I cursed and fought the crack with all my might. The rock dug into the backs of my hands, and shredded my ankles as my feet fought for purchase.

Panting and fuming I reached the roof. I reached out and over and found a good hold and held on to it with all my might, shaking and thrashing about as I slugged and bumped myself up and over to it. I pawed for other holds and finally - to my amazement I'm sure as much as Matt's - I got over the bastard.

Summit fever was taking control of us.

Another crack led over the ledge. My widest cams were barely big enough to protect it. I only had 3 cams left and 40 or so feet of climbing until the crack got small enough to set a belay. Finally I set the anchor with my 3 remaining cams. Matt jugged up and set off into the remaining part of the chimney. The weather had been changing rapidly all day, and it was beginning to snow. Another crack led over the ledge. My widest cams were barely big enough to protect it. I only had 3 cams left and 40 or so feet of climbing until the crack got small enough to set a belay. Finally I set the anchor with my 3 remaining cams. Matt jugged up and set off into the remaining part of the chimney. The weather had been changing rapidly all day, and it was beginning to snow.

He led for 20ft until he pulled out a roof and was gone from view. Within those twenty feet, he struggled and fought more than any other time I'd ever seen him climb. The crack was wider than we had gear for and it was snowing. He grunted and shoved his body into the overhang. The rope moved through my belay device slowly until I could barely make out a murmur that he was off belay. I jugged up the heinous body flare, out the roof, through a vertical crack then up and over onto a ledge that led to the summit! I pulled up the rope behind me, draped it over my shoulders and meandered through all the loose rock that was between Matt and I.

We shot off all of our film. In the time it took me to follow the pitch the storm had cleared enough that there was blue sky above us. We hadn't seen blue sky in days.

After fifteen minutes we started to get ready to go down.

"What time is it?" Matt asked.

"3:15." I think we might be able to make it all the way down if the weather holds."

Matt set a few hexes and we descended. We left hexes and stoppers all the way back down, and retrieved the cams we had left before. By the time we reached the ground, we had not once used the bolt kit.

It started to rain as we began the hike. The talus was very hard to walk on and we slipped and fell almost constantly. Our packs weighed heavily on us and dug into our shoulders. At around 10PM we got back to camp. We were useless: dehydrated, hungry, weak, exhausted. Matt's face showed that he had fought a nasty battle with the haulbag the whole way home.

For the next 4 days it snowed. We were nearly out of food by this point, resorting to peanut butter and potato flakes as our sole nourishment. We called Warren LaFave at the lodge with our rented satellite phone and he said that the storm was so bad that Whitehorse - nearly 200 miles south of them was socked in. Matt, who was skinny enough before the trip, was concerned that he couldn't get much skinnier.

The 16th of August, the day we were supposed to fly out proved to be the worst of any of the previous four. At noon we started to hear the familiar sound of an engine. 'Can't be....' Just then the familiar yellow helicopter appeared out of the clouds. Wes, our pilot, took us to Glacier Lake and dropped us off to wait for the float plane to pick us up. Then he flew up to the Cirque of the Unclimbables and picked up John Sherman - the rest of his team had already flown out - he was stuck by himself for two days because the storm had gotten too bad. The whole flight back we sat quietly peering out the windows and listening to our grumbling stomachs.

After Wes landed, he led Matt and I to the kitchen and told us we could have anything we wanted to eat. Matt ate four plates of food, I chocked down two before pains in my stomach forced me to stop - my belly had shrunk. We took showers next, and scrubbed off a month's worth of grime.

|